Earlier this year, the National Zoo in Washington D.C. got two new pandas, Bao Li and Qing Bao. Many celebrated the return of the pandas, and just as many others dreaded it. This dread may stem from the historical inhumane and unethical treatment of pandas in captivity in the United States. Additionally, this chain of harm might continue, as the National Zoo plans to breed the two.

The artificial breeding of pandas is extremely dangerous and harmful. Artificial breeding can cause sickness, permanent damage to a panda’s reproductive system, and has even killed a male panda in Japan in 2010. But why do zoos choose this invasive breeding tactic instead of natural breeding? Pandas are extremely picky with who they mate with, and for good reason. Many male pandas are extremely aggressive and often incompetent. Some would point out that the world needs more pandas and that these breeding techniques keep the panda population alive and thriving, but, on the contrary, this breeding only benefits captive pandas, as no pandas in American or European zoos have ever been released back into the wild.

The Panda Diplomacy Program started in 1941 between the United States and China.

This program allows host countries to “lease” a pair of pandas from China for a fee of around 1 million dollars. These lease agreements typically last around 10 years. A portion of the leasing fee goes directly to wildlife conservation efforts in China. These efforts also contribute to a more genetically diverse breeding population, as there are only around 700 pandas in captivity. However, while the program may seem beneficial, many zoos didn’t share the same goal of conservation and instead saw it as a way to get more visitors, prestige, and merchandise sales.

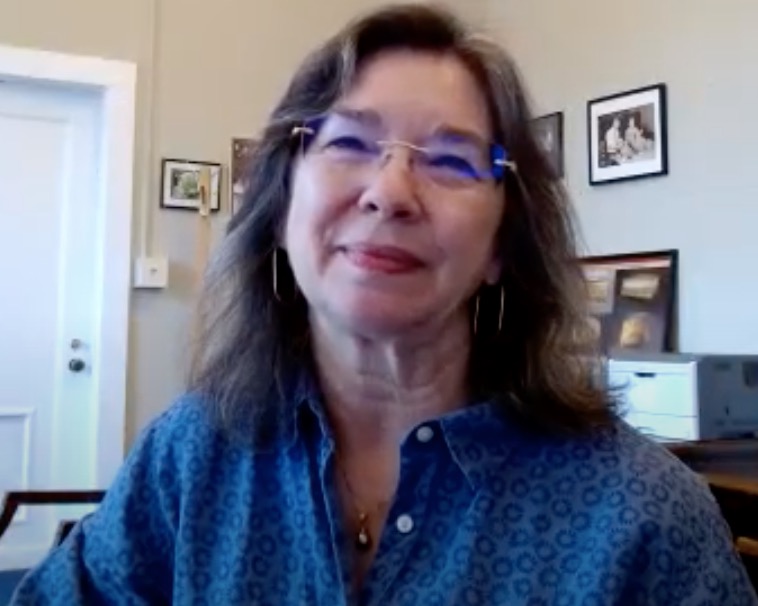

The money aspect is clear as day, as a compelling example is our own National Zoo. In 1999, the National Zoo launched a 13 million dollar fundraising campaign. 10.5 million was spent on what we now know as the “education center.” This money was labeled as a donation to the zoo, so it could get around having to donate the money to conservation efforts, as that was one of the requirements of the pandas on loan. Kati Loeffler, a veterinarian who worked at a panda breeding center in China during the program’s early years, stated “I remember standing there…I realized, ‘Oh my God, my job… is to turn the well-being and conservation of pandas into financial gain.’” This use of pandas as objects for financial gain has led to many cases of panda neglect and abuse. In 1987, a panda had to do a balancing act at the San Diego Zoo, this cruel treatment happened less than 40 years ago. One of the most recent and well-known cases was a few years ago. Two Pandas at the Memphis Zoo, Ya Ya and Le Le, suffered from zoochosis, a term for abnormal and repetitive behaviors in animals caused by captivity, and malnutrition between the years of 2003 and 2023. Ya Ya and Le Le were forced to live in small internal enclosures and share a single external yard for almost two decades. Pandas are solitary animals so they had to take turns using the yard. After medical examinations in 2021 and January 2022, it was concluded that both pandas are underweight, especially Ya Ya. She also had fur loss due to chronic Demodex mites. Le Le had several broken molars as well. The Memphis Zoo argued that it was just old age, but at the time the two were some of the youngest pandas in the United States at that time; the others looked way better than Ya Ya and Le Le. Two key reasons that many thought the pandas were malnourished was because their diet wasn’t adjusted for their age and the bamboo they were fed was yellow and appeared stale.

In 2021, an international group called Panda Voices created a movement called #FreeYayaLele. This movement collected more than 85,000 signatures for a petition that wanted the release of the two giant pandas at the Memphis Zoo. Even an American singer, Billie Ellish, tweeted her support. In December 2021, it was announced that they would be returned to China in the spring. Heartbreakingly, Le Le passed before getting the life he deserved.

I want to ask you the questions every animal advocate asks themselves when it comes to pandas. Is it a good thing that there are pandas back at the National Zoo? Do we want to support the pandas in this climate? Is education worth the captivity of animals? Are we saving endangered species or killing them in other ways? If we are, how do we solve these issues? To be honest, I don’t know, but I do know these questions should be answered sooner rather than later. Hopefully by my generation, and hopefully before Le Le and Ya Ya’s story repeats with Bao Li and Qing Bao.