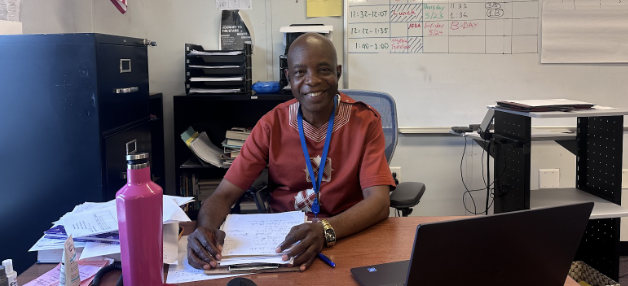

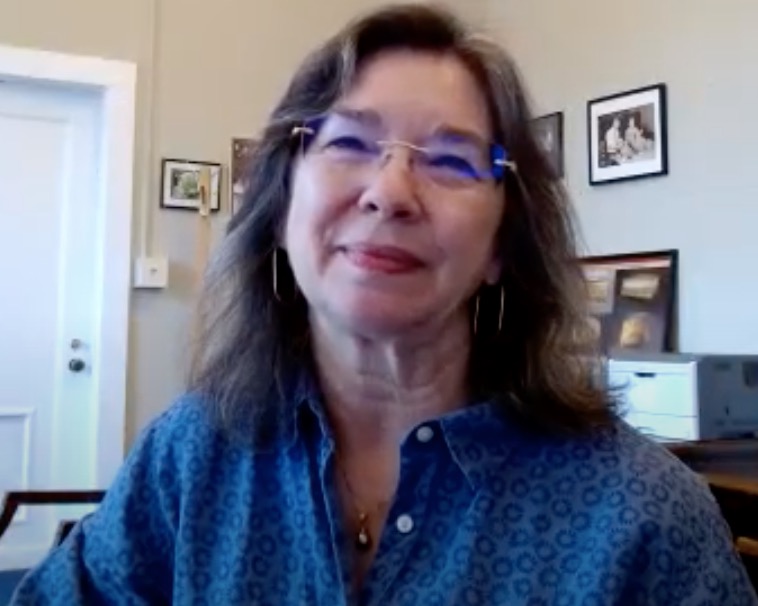

It was a bright sunny day in East Africa and Jennifer Clark was about to make one of her coolest discoveries yet: the skeleton of a fossil elephant shrew. Jennifer Clark is a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian. When one thinks of a paleoanthropologist one likely takes the prefix “paleo-” to mean ancient and the word “anthropologist” to mean a specialist in humanity and derives that a paleoanthropologist is someone who specializes in ancient humans. While this is true, it’s not the whole truth. Paleoanthropologists specialize in often very different and niche fields trying to understand how early humans evolved and how they adapted to their ever-changing environment. In Clark’s case, she specializes in plants and animals that lived alongside our ancestors between 200,000 and 1 million years ago. She’s also a museum specialist. With her skill set, she’s able to go on digs in the summer months in Kenya and study the small vertebrate animal fossils that are found during said excavations during the winter months in Nairobi, “it’s kind of like a detective’s story.” While there, she helps the museum create exhibits that are easy to understand while still presenting the necessary information.

The world is always evolving, both genetically and technologically. With the recent rise of AI, Clark hopes that it will help usher in a new age of paleo-anthropologists. An age in which with a few images, a robot can pinpoint where exactly a team should dig. This, she hopes, will greatly speed up the process and allow for “more time to be spent studying rather than searching.” Beyond AI, techniques are getting a lot better which will hopefully shed more light on the way early humans lived. Technology is always changing, and with it careers are evolving.

Clark graduated from the University of Georgia and since then has only worked at the Smithsonian. She is in a unique position where she is one of the very few people not to have an advanced degree on her team. She’s worked her way up. Her career, however, is not a typical one as they are rarely as linear. Very rarely does someone work in one place and just go upward with some horizontal career shifts along the way. Often, a career is like evolution, “all these branches to our ancestry and it’s not like this linear progression.” With these branches, it’s quite possible to branch into a completely different tree. The tree, while different from the one studied, that might lead to a more fulfilling life. Sometimes, it’s better to go with the flow and see what works and what doesn’t instead of just containing oneself to a box they defined in their 20s.

It’s also possible that going with the flow leads you right back onto the path that one set out on, like in Clark’s case. While she majored in biology, she also had a passion for art, so she took a lot of art classes. Even though she worked as a researcher, the Smithsonian needed artists to help design the exhibits and help bring knowledge from the papers to the masses. Clark was able to use her passion as an artist to branch out from her major and help design and provide content exhibits and websites. This is what helped her become a museum specialist. In today’s money-driven world, it can become easy to see the dollar as the only thing that matters and disregard your own interests and passions if they aren’t profitable. In Clark’s case, however, she was able to incorporate her less bountiful passions into a well-paying career. Just because someone’s passion isn’t profitable doesn’t mean it isn’t worth exploring.

Throughout Clark’s time as an anthropologist, she’s learned and done a lot, however, I think the best thing that someone can take away from it is not what she’s done, but rather how she’s done it. She went into her team being one of the only people without an advanced degree and was able to build her way up while still incorporating her passions. Clark’s career helps show how powerful doing something you enjoy can be and that money and interests can often intertwine.