Back in late September, scientists at the Ocean University of China published a report detailing a new virus discovered in the depths of the Mariana Trench that, to our best knowledge, “… is the deepest known isolated phage in the global ocean,” according to marine virologist Min Wang, who was involved in the study.

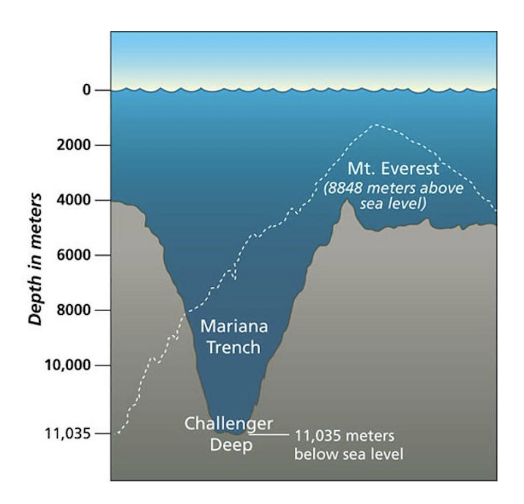

The Mariana Trench

Located in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, the Mariana Trench is the deepest ocean trench on Earth. Formed by a collision of adjacent tectonic plates, where one plate is forced beneath the other, the trench measures over 1,580 miles (2,540 km) long with an average width of 43 miles (69 km). Its depth had been a challenge to measure for decades, with the deepest estimates exceeding 36,000 feet (10,973 meters) deep.

vB_HmeY_H4907

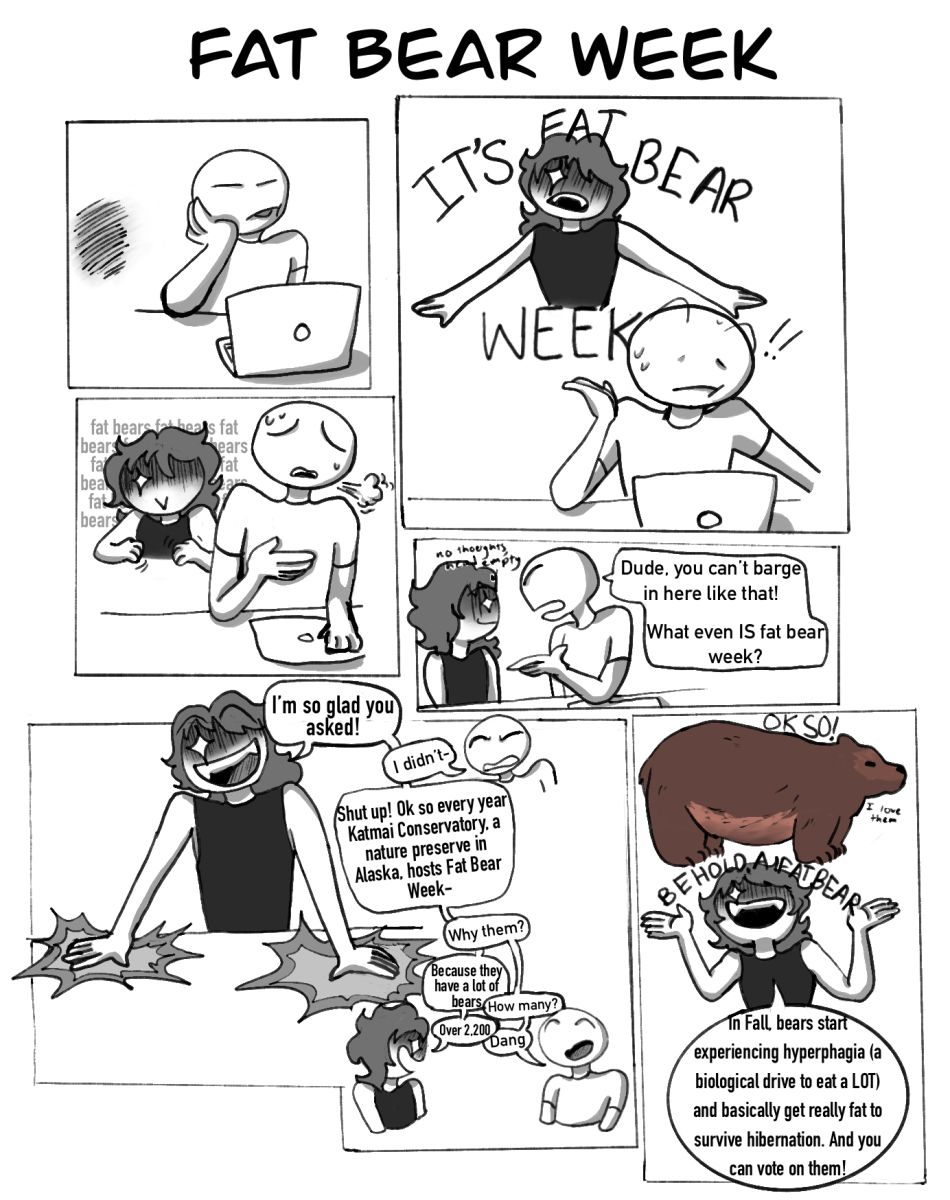

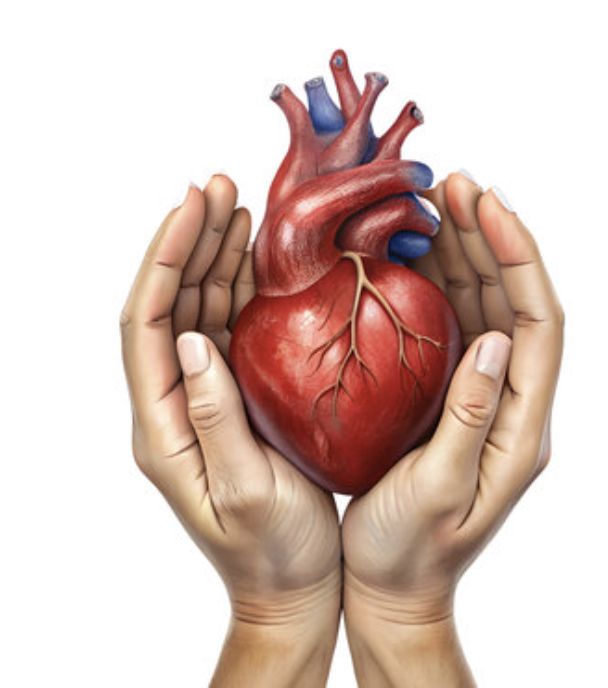

Researchers were able to extract sediment from around 8,900 feet (2713 meters) down the trench, from which the virus was then isolated. Identified as vB_HmeY_H4907, the virus is what’s known as a bacteriophage, a subset of viruses that infect and replicate in bacteria. The American Society for Microbiology reports that it “…infects bacteria in the phylum Halomonas, which are often found in sediments from the deep seas and from hydrothermal vents, geyser-like openings on the seafloor that release streams of heated water.” In addition to living in such a unique environment, the bacteriophage is also a lysogenic virus.

Lytic vs. Lysogenic

Typically, when thinking about viruses, people talk about those in the “lytic cycle.” The lytic cycle begins when a virus first attaches itself and inserts its DNA, or genome, into whatever cell it plans to take over. From here, it begins to deteriorate the host cell’s existing genome, taking over its replication mechanisms. The virus will then begin to replicate both its genome and its proteins until it has assembled many new copies of itself. The cycle finishes by killing the host cell and releasing the new clones, which will then repeat this process until the virus is killed off or the organism dies.

But there is another way for viruses to reproduce with the “lysogenic cycle,” which is how vB_HmeY_H4907 replicates. This cycle begins the same way as its counterpart, with the virus attaching to the cell and inserting its DNA. Instead of degrading the original genome, however, the viral DNA is integrated with the cell. This results in the viral genome being replicated alongside the cell, meaning that the host is not killed at the end of the process. However, there is always the chance that a virus can go from being lysogenic to lytic, causing the cell death typically associated with infections.

Why does this matter?

Readers may be thinking, “Why do we care about a virus in one of the most remote locations on earth? It can’t even infect humans!” However, this discovery could lead to a new understanding of microbial life within these extreme environments. Genetic analysis of vB_HmeY_H4907 suggests there is a whole unknown viral family in the deep ocean, as well as evidence of it co-evolving with its host organism. With work in isolating viruses both in deep oceans and polar regions, the team plans to keep searching for new pathogens as, according to Wang, “Extreme environments offer optimal prospects for unearthing novel viruses.”